Prayer (salah) holds the highest and most noble position among physical acts of worship in Islamic law, second only to the declaration of faith (Shahadah). For Muslims seeking to perfect their daily worship, understanding the Sunnah prayers Shafi’i fiqh is profoundly essential.

In the extensive literature of Shafi’i jurisprudence, specifically as expounded by Shaykh al-Islam Zakariyya al-Ansari in his authoritative text, Asna al-Matalib, prayers are fundamentally divided into obligatory (fardh) and voluntary (sunnah or tathawwu’). Voluntary prayers encompass a wide variety of rulings, structural conditions, and a meticulously detailed hierarchy of virtues. This article provides an academic and comprehensive examination of these prayers, perfectly tailored for seekers of knowledge striving to emulate the pious predecessors (salafus shalih).

Terminology of Voluntary Prayers in Islamic Jurisprudence

Within the scholarly Islamic tradition, jurists employ several terms to denote additional acts of worship beyond the mandatory obligations. Shaykh al-Islam Zakariyya al-Ansari clarifies this linguistic breadth:

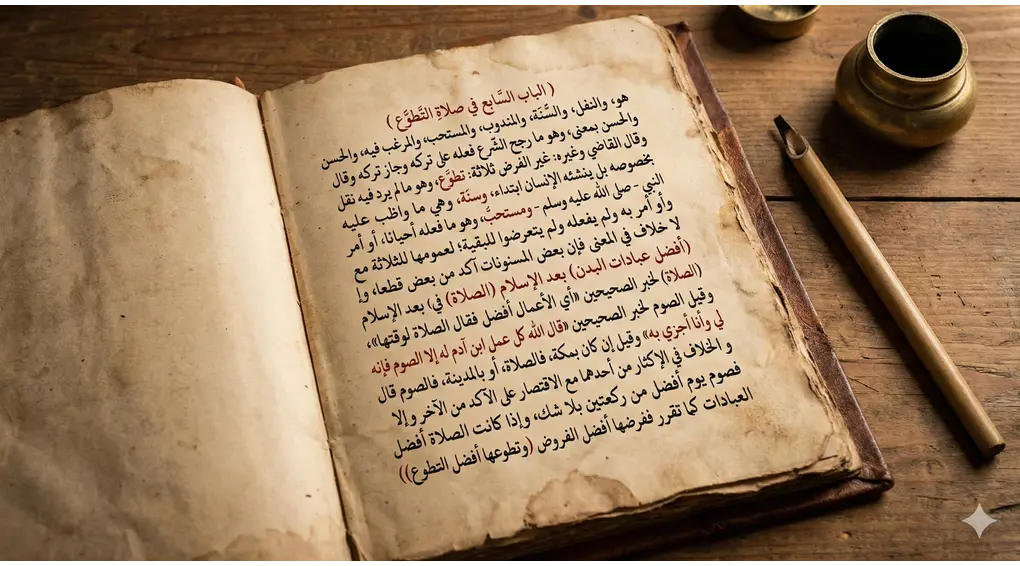

قوله: (الباب السابع في صلاة التطوع) هو، والنفل، والسنة، والمندوب، والمستحب، والمرغب فيه، والحسن بمعنى، وهو ما رجح الشرع فعله على تركه وجاز تركه

Meaning: (The Seventh Chapter on Tathawwu’ Prayer) The terms tathawwu’, nafil, sunnah, mandub, mustahabb, muragghab fih, and hasan share the exact same meaning: an act that the Shari’ah prefers to be performed rather than omitted, yet its omission remains legally permissible.

However, Al-Qadhi and other prominent scholars offer a more specific categorization, dividing non-obligatory worship into three primary conceptual tiers:

- Tathawwu’: An act of worship that lacks specific scriptural evidence regarding its recommendation, originating purely from a person’s initial initiative to draw closer to Allah.

- Sunnah: An act of worship that the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) consistently maintained and performed routinely.

- Mustahabb: An act of worship that the Prophet (ﷺ) performed occasionally, or one that he commanded his followers to do but did not physically perform himself.

Why is Prayer the Most Virtuous Physical Act of Worship?

The text of Asna al-Matalib firmly establishes that prayer is the supreme physical act of worship after embracing Islam. This conclusion is anchored in a hadith from the Sahihayn (Bukhari and Muslim): “Which deed is the best? He [the Prophet] replied: Prayer at its appointed time.”

Scholars have historically debated the comparative virtue between prayer and fasting. Some argue that fasting is superior based on the Hadith Qudsi: “Every deed of the son of Adam is for him, except fasting; it is for Me, and I shall reward for it.” Imam an-Nawawi, in Al-Majmu’, provides a geographical nuance to this debate: If a person resides in Makkah, multiplying prayers (and Tawaf) is superior. Conversely, if one is in Madinah, multiplying fasting is prioritized.

Regardless of this specific geographic distinction, the overarching jurisprudential maxim asserts that “fasting for one day is better than praying two rak’ahs, without a doubt.” Consequently, since the obligatory prayer is the best of obligations, the voluntary prayer (tathawwu’) is conclusively the best of voluntary physical worship.

Congregational Sunnah Prayers Shafi’i Fiqh Hierarchy

Shafi’i jurisprudence categorically divides tathawwu’ prayers into two major sections: those prescribed to be performed in a congregation (jama’ah) and those prescribed individually (munfarid).

Congregational Sunnah prayers occupy a higher, more virtuous position (afdhal) compared to individual ones. The hierarchy is established as follows:

A. Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha Prayers (Idain)

قوله: (وأفضله العيدان) لشبههما الفرض في الجماعة وتعين الوقت

Meaning: (And the most virtuous of them are the two Eid prayers) due to their resemblance to the obligatory prayers regarding the congregation and the specific designated time.

A scholarly divergence exists regarding which of the two Eids holds superiority. ‘Izz al-Din ibn ‘Abd al-Salam argued that Eid al-Fitr is superior because its command for Takbir is explicitly stated in the Qur’an (Al-Baqarah: 185). However, Imam al-Zarkashi posited that Eid al-Adha is stronger because it occurs in a sacred month and encompasses the monumental rites of Hajj and animal sacrifice (Qurban).

B. The Eclipse Prayers (Kusuf and Khusuf)

Following the Eid prayers are the Solar Eclipse (Kusuf) and then the Lunar Eclipse (Khusuf).

قوله: (ثم الكسوف) للشمس (ثم الخسوف) للقمر لخوف فوتهما بالانجلاء كالمؤقت بالزمان

Meaning: (Then the Kusuf) for the sun (then the Khusuf) for the moon, due to the fear of missing their time if the eclipse clears, placing them in the status of time-bound prayers.

The Solar Eclipse is prioritized over the Lunar Eclipse because the sun is consistently mentioned before the moon in the Qur’an and Hadith, and the sun’s benefit to earthly life is tangibly greater.

C. The Prayer for Rain (Istisqa’)

The Istisqa’ prayer is positioned sequentially after the eclipse prayers. The Prophet (ﷺ) occasionally omitted the Istisqa’ prayer under certain conditions, which contrasts with the eclipse prayers, which he never neglected when the celestial phenomena occurred.

D. The Tarawih Prayer

Tarawih prayer holds a majestic status during the holy month of Ramadan. The majority of Shafi’i scholars determine that Tarawih is superior to the Rawatib prayers (with the exception of the two Sunnah rak’ahs of Fajr and the Witr prayer).

قوله: (وهي عشرون ركعة) بعشر تسليمات في كل ليلة من رمضان

Meaning: (And it is twenty rak’ahs) with ten salutations (salam) every night in Ramadan.

The evidence for twenty rak’ahs stems from the consensus (ijma’) of the Companions during the caliphate of Umar ibn al-Khattab, who gathered the men behind Ubayy ibn Ka’ab and the women behind Sulayman ibn Abi Hathmah.

A strict condition for the validity of Tarawih is concluding with a salam after every two rak’ahs. If one prays four rak’ahs continuously with a single salam, the Tarawih is invalid as it contradicts the established narrations—unlike the Sunnah of Dhuhr or Asr, which are validly performed as four rak’ahs with one salam.

Non-Congregational Sunnah Prayers

The second major category encompasses prayers primarily designed to be performed individually in solitude (munfarid). This practice preserves sincerity and protects the heart from ostentation (riya’).

A. The Witr Prayer

The Witr prayer is undisputedly the most virtuous of the non-congregational Sunnah prayers.

قوله: (وأفضلها الوتر) لخبر «أوتروا فإن الله وتر يحب الوتر» رواه الترمذي

Meaning: (And the most virtuous of them is the Witr) based on the hadith: “Perform the Witr, for indeed Allah is Witr (One/Odd) and He loves the Witr.” (Narrated by At-Tirmidhi).

The time for Witr begins after the completion of the Isha prayer and extends until the second dawn (Fajr). It is highly recommended to separate (fashl) the Witr, meaning one performs a salam after every two rak’ahs and concludes with an independent single rak’ah.

B. The Rawatib Prayers (Accompanying Obligatory Prayers)

These are the prayers attached to the obligatory prayers. The Highly Emphasized (Mu’akkad) Rawatib consist of 10 rak’ahs:

- 2 rak’ahs before Fajr (The highest status among Rawatib).

- 2 rak’ahs before Dhuhr.

- 2 rak’ahs after Dhuhr.

- 2 rak’ahs after Maghrib.

- 2 rak’ahs after Isha.

The Non-Emphasized (Ghayr Mu’akkad) Rawatib include 4 rak’ahs before Asr, an additional 2 rak’ahs before and after Dhuhr, and 2 quick rak’ahs before Maghrib and Isha.

Summary Table of Sunnah Prayer Virtues

To provide a clearer structural overview, below is the hierarchy based on Shafi’i texts. For those interested in the profound reasoning behind this specific ordering, you may explore the detailed hierarchy of sunnah prayers on our fiqh portal.

| Category | Rank of Virtue (Based on Asna al-Matalib) | Additional Academic Notes |

| Congregational | 1. Eid al-Fitr & Eid al-Adha | Closely approaches the legal status of Fardh Kifayah. |

| 2. Solar Eclipse (Kusuf) | Prioritized over the lunar eclipse. | |

| 3. Lunar Eclipse (Khusuf) | ||

| 4. Rain Prayer (Istisqa’) | Elevated due to the congregation requirement. | |

| 5. Tarawih | Superior to Rawatib (excluding Fajr & Witr). | |

| Individual | 1. Witr | Minimum 1, maximum 11 rak’ahs. |

| 2. Two Rak’ahs of Fajr | The highest-ranking Rawatib. | |

| 3. Remaining Mu’akkad Rawatib | The other 8 emphasized rak’ahs. | |

| 4. Dhuha Prayer | Time-bound to the morning/forenoon. | |

| 5. Cause-bound Prayers | Tawaf, Ihram, Greeting the Mosque, etc. |

Time and Cause-Bound Sunnah Prayers

1. Dhuha Prayer

Its timeframe begins when the sun rises to the height of a spear and lasts until the sun reaches its zenith (istiwa). The minimum is 2 rak’ahs, the lowest level of perfection is 4, and the maximum is 8 rak’ahs (according to the strongest opinion in Asna al-Matalib). To properly establish this morning routine, we recommend reading the comprehensive guide to Dhuha prayer for specific recitations and protocols.

2. Greeting the Mosque (Tahiyyatul Masjid)

Performed as two rak’ahs upon entering a mosque to show reverence (ta’dhim) to the sacred space.

(وتفوت بجلوسه)

Meaning: (And its recommendation is lost if he sits down).

If a person enters the mosque and intentionally sits before praying, the recommendation to perform Tahiyyatul Masjid is forfeited, unless the sitting was due to forgetfulness and the duration was brief.

3. Istikharah, Hajat, Taubat, and Tasbih Prayers

- Istikharah: It is advised to recite Surah Al-Kafirun in the first rak’ah and Al-Ikhlas in the second. The exact prophetic wording to seek divine guidance can be found in the dua for Istikharah prayer.

- Hajat: A specific two-rak’ah prayer performed when one has a pressing need. The profound spiritual benefits and correct formatting are thoroughly discussed in the complete guide to Hajat prayer.

- Taubat: Two rak’ahs performed whenever a servant falls into sin, followed by sincere repentance. For a profound understanding, study the Taubat Nasuha prayer with its evidence, procedures, and dua.

- Tasbih: A four-rak’ah prayer containing the glorification formula 75 times per rak’ah.

Making Up (Qadha) Missed Sunnah Prayers

Shafi’i fiqh establishes that voluntary prayers bound by a specific timeframe (ma lahu waqt) are recommended to be made up if missed.

قوله: (يقضي) ندبا (من النوافل ما له وقت) كالعيد، والضحى ورواتب الفرائض

Meaning: (It is recommended to make up) the voluntary acts that have a set time, such as Eid, Dhuha, and the Rawatib of obligatory prayers.

This is directly based on the Prophet’s (ﷺ) action of making up the two Sunnah rak’ahs of Fajr after the sun had risen, and making up the post-Dhuhr Rawatib after the Asr prayer.

Etiquette and Virtues of the Night Vigil (Qiyam al-Lail)

Performing Sunnah prayers at night (Qiyam al-Lail or Tahajjud) is spiritually loftier than praying during the day. Furthermore, performing them at home is superior to praying in the mosque, as it purifies the heart from the disease of showing off (Riya’) and nurtures absolute sincerity (Ikhlas).

قوله: (ونصفه الأخير) إن قسمه نصفين (أو ثلثه الأوسط) إن قسمه أثلاثا (أفضل)

Meaning: (And the latter half of it) if he divides the night into two, (or the middle third of it) if he divides it into three, (is the most virtuous time).

It is considered mildly disliked (makruh) to abandon an established routine of Tahajjud without a valid excuse, to protect the believer from spiritual lethargy (futur).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is it permissible to change the intended number of rak’ahs in the middle of an absolute (mutlaq) Sunnah prayer?

If a person formulates an intention for an absolute Sunnah prayer without specifying a number, they may perform the salam at any time. However, if they initially set an intention for 4 rak’ahs, they may increase or decrease it only if they change their intention internally before rising. If they intend 4 rak’ahs but deliberately perform salam after 2 without updating the intention in their heart, the prayer is invalidated according to Asna al-Matalib. Navigating this requires a solid grasp of the levels of intention in prayer.

Should I prolong the Tahiyyatul Masjid prayer if the Iqamah is imminent?

It is disliked (makruh) to busy oneself with Tahiyyatul Masjid if the congregational obligatory prayer is about to commence. This is based on the Sahih narration: “When the prayer has been established (Iqamah is called), there is no prayer except the obligatory one.”

Which is better during Tahajjud: praying many rak’ahs or standing for a long time?

Prolonging the standing (Qiyam) by reciting lengthy Surahs is deemed more virtuous and superior than merely increasing the number of rak’ahs and prostrations during the night vigil.

Conclusion

Understanding the diverse classifications and precise hierarchy of the Sunnah prayers Shafi’i fiqh provides a clear roadmap for Muslims to organize their daily spiritual routines. The classical text Asna al-Matalib delivers rigorous principles on worship priorities—from highly communal prayers like Eid and Tarawih to the majestic individual devotions like Witr and Tahajjud in the depths of the night.

May this academic exposition of Shafi’i jurisprudence facilitate our journey toward perfect servitude, protect us from spiritual stagnation, and ensure our inner state remains deeply connected to Allah the Exalted through valid, authentic voluntary worship guided by the pious predecessors.

Reference

Zakariyā al-Anṣārī, Asnā al-Maṭālib fī Sharḥ Rawḍ al-Ṭālib, with annotations by Aḥmad al-Ramlī, edited by Muḥammad az-Zuhrī al-Ghamrāwī (Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿah al-Maymānīyah, 1313 AH; repr. Dār al-Kitāb al-Islāmī), vol. 1, pp. 200–208.