The month of Ramadan, or days of voluntary fasting, often raises a fundamental question for us: how many are the pillars of fasting actually? Is it enough to simply restrain from hunger and thirst? Or are there other things that determine the validity of our worship?

Many people think the pillars of fasting are 2, namely intention and abstaining. However, if we open classical fiqh books, especially in the Shafi’i school of thought, the discussion turns out to be more detailed. One of the main references often studied in Islamic boarding schools is the book Safinatun Naja and its commentary, Nailur Raja’.

In this article, we will thoroughly examine the number of pillars of fasting, the difference between the intention for obligatory and voluntary fasting, and the original text from classical Islamic texts so that our understanding becomes more solid.

What are the Actual Arkān of Fasting?

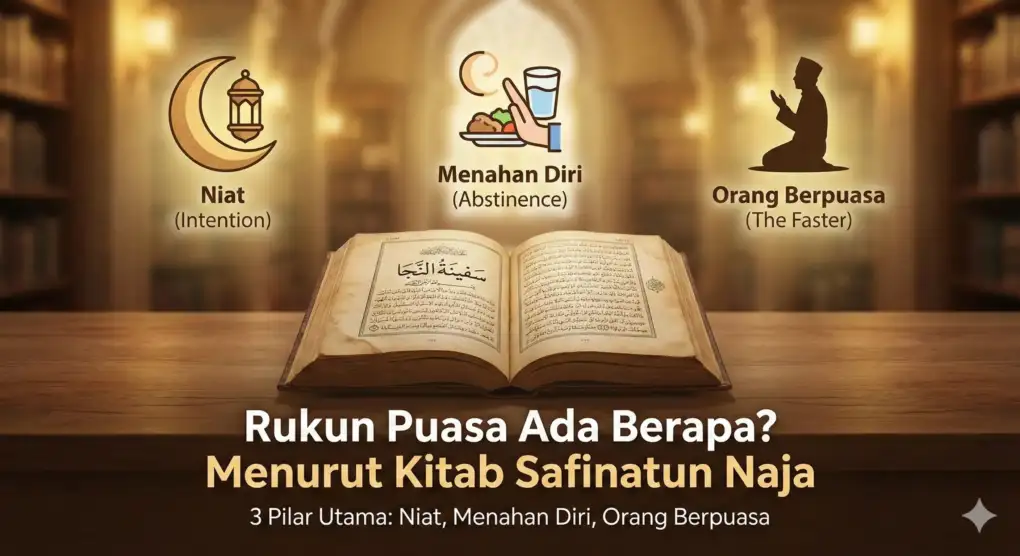

In the study of the pillars of fasting in Islam, specifically referring to the Shafi’i school in the book Nailur Raja’ Syarh Safinah an-Naja, it is explicitly stated that there are three pillars of fasting.

The author of the book explains:

“The pillars, without which the essence of fasting will not be realized, are three.”

Thus, according to this reference, there are three pillars. These three things are the supporting pillars. If one is missing, then the fast is considered invalid or did not occur.

Let’s dissect one by one the pillars of fasting along with their explanation.

Detailed Explanation of the 3 Arkān of Fasting

Here is a detailed explanation of the pillars of fasting according to the book Safinatun Naja:

1. Intention (The First Pillar of Fasting)

The first pillar of fasting is intention. The position of intention is very crucial because it distinguishes between worship and merely a habit of abstaining from food (diet). However, there are different rules between the pillars of Ramadan fasting (obligatory) and voluntary fasting.

For obligatory fasting (Ramadan, Qadha, Nazar, Kafarat), the intention (Tabyit) must be made at night. The time frame extends from sunset (Maghrib) until the dawn of true dawn (Subuh).

Important Points about Intention:

- Obligatory Every Night: You must have the intention every night to fast the next day.

- Solution for Forgetting the Intention: The book Nailur Raja’ provides an interesting tip. On the first night of Ramadan, it is recommended to intend to fast for the entire month by following (taqlid) the opinion of Imam Malik. The purpose is as a “backup”. If one night we forget to intend, the fast for that day is still valid according to Imam Malik, so we do not need to make it up1.

- More Flexible Voluntary Fasts: Regarding the pillars of voluntary fasting, the intention (niat) can be made during the day before Zuhr time (zawal), as long as one has not done anything that invalidates the fast since morning, such as eating or drinking.

2. Abstaining from Things That Nullify the Fast (Mufattirat)

The pillars of fasting are restraining oneself (al-imsak) from everything that invalidates it. This includes eating, drinking, sexual intercourse, or inserting anything into bodily orifices.

However, not all violations immediately invalidate the fast. This book provides details of very fair conditions. A person’s fast is only considered broken if they do so under three conditions:

- Reminder (Dzakiran): He is aware that he is fasting. If he eats due to genuine forgetfulness, his fast remains valid.

- Voluntarily (Mukhtaran): Not due to coercion. If someone is forced to drink under threat of weapon, their fast is not invalidated.

- Awareness of the Prohibition (‘Aliman): He knew that the act was Ḥarām to perform while fasting.

What about those who are unaware of the law? There is a term Jahil Ma’dzur (the ignorant who are excused). For example, a new convert to Islam or someone who lives far in the hinterland and has no access to scholars. If they eat because they are unaware that it is Ḥarām during fasting, their worship remains valid.

But, if you live in a city, have internet access, and are close to a mosque but are lazy to learn, then you violate the fasting rules because of “ignorance,” then that ignorance is not excusable (ghairu ma’dzur) and your fast is invalid.

3. The Fasting Person (Ash-Shaim)

It may sound unique, why is a person included as a pillar? The pillars of fasting are elements that must be present for the fast to be valid.

In the book Nailur Raja syarah Safinatun Naja, it is explained that fasting is ‘adamiyyan in nature (characterized by non-existence/restraint). Fasting is “not eating” and “not drinking.” This act of “not doing” has no physical form that can be seen.

Unlike prayer which has visible movements of bowing and prostration (visible to the eye), fasting can only be understood if there is someone fasting (Ash-Shaim). Just like buying and selling, a transaction is impossible without a seller and a buyer. Therefore, the existence of the “Fasting Person” with its conditions (Muslim, sane, and free from menstruation/postpartum bleeding) becomes the third pillar.

Table of Differences Between the Intention for Obligatory and Sunnah Fasting

To better understand the technical differences in the pillars of fasting, see the intention section, please refer to the following table:

| Aspect | Obligatory Fasting (Ramadhan, Qadha, Nazar) | Sunnah Fasting (Monday-Thursday, Arafah, Shawwal) |

| Time of Intention | Obligatory at night (Maghrib – Fajr). | Permissible at night, permissible during the day before Dhuhur. |

| Condition of Daytime Intention | Not applicable (daytime intention is invalid). | The condition is not having committed any fasting invalidators since Fajr. |

| Renewal of Intention | Obligatory to renew every night. | Sufficient to intend when wanting to fast. |

Original Text from the Reference Book

For those of you who are studying Arabic texts or need authentic references, here is the original excerpt from the book Nailur Raja’ Syarh Safinatun Naja pages 273-274 regarding this chapter:

فَصْلٌ : ( أَرْكَانُهُ ثَلَاثَةٌ ) : المعنى : أَنَّ الأَركان التي لا تتحقق ماهية الصومِ إلا بها : ثلاثة ( نِيَّةٌ لَيْلاً لِكُلِّ يَوْمٍ فِي الْفَرْضِ )… ( وَتَرْكُ مُفَطَّرٍ ذَاكِراً مُخْتَاراً غَيْرَ جَاهِلِ مَعْذُورٍ )… ( وَصَائِمٌ ) المعنى : أَنَّ الرَّكْنَ الثَّالِثَ مِنْ أَركَانِ الصوم : الصَّائِمُ

This text affirms that the structure of the worship of fasting is built upon those three Arkān.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions About the Pillars of Fasting

Here are some frequently asked questions that appear on search engines related to this topic:

Why do some say there are 2 pillars of fasting?

The opinion stating that the pillars of fasting are 2, namely intention and abstaining, is not necessarily incorrect. This opinion often combines “the fasting person” as a mandatory condition or a valid condition, rather than a pillar in and of itself. However, in the detailed Shafi’i jurisprudence as found in Safinatun Naja, “the fasting person” is separated as the third pillar due to the abstract philosophical nature of fasting.

Does eating while forgetful break the pillars of fasting?

No. As explained above, one of the conditions for a violation to be considered invalidating is Dzakiran (being in a state of awareness). If you genuinely forget, the pillars of fasting are not broken, and you may continue your fast.

What are the requirements for the validity of the intention to fast during Ramadan?

The primary requirements are Tabyit (making the intention at night) and Ta’yin (specifying the type of fast, for example: “I intend to fast tomorrow to fulfill the obligatory fast of Ramadan”).

Understanding the number of pillars of fasting and its details is not merely theoretical, but the key to ensuring our worship is accepted. By knowing that the first pillar of fasting is a sincere intention, and understanding the limits of restraint, we can practice worship with greater peace and confidence. May this explanation from the book Safinatun Naja be beneficial to your worship.

Referensi & Catatan Kaki

Al-Syāṭirī, Aḥmad bin ‘Umar. Nayl al-Rajā fī Syarḥ Safīnat al-Najā. Jeddah: Dār al-Minhāj, no date.

- Aḥmad bin ‘Umar al-Syāṭirī, Nayl al-Rajā fī Syarḥ Safīnat al-Najā, (Jeddah: Dār al-Minhāj, t.t.), hlm. 273. ↩︎