For Muslims, the sound of the Adhān is a very familiar call to the ear. Five times a day, this call echoes from mosques as a marker of prayer times. But how deeply do we understand the meaning of the Adhān and Iqamah, as well as the history behind them?

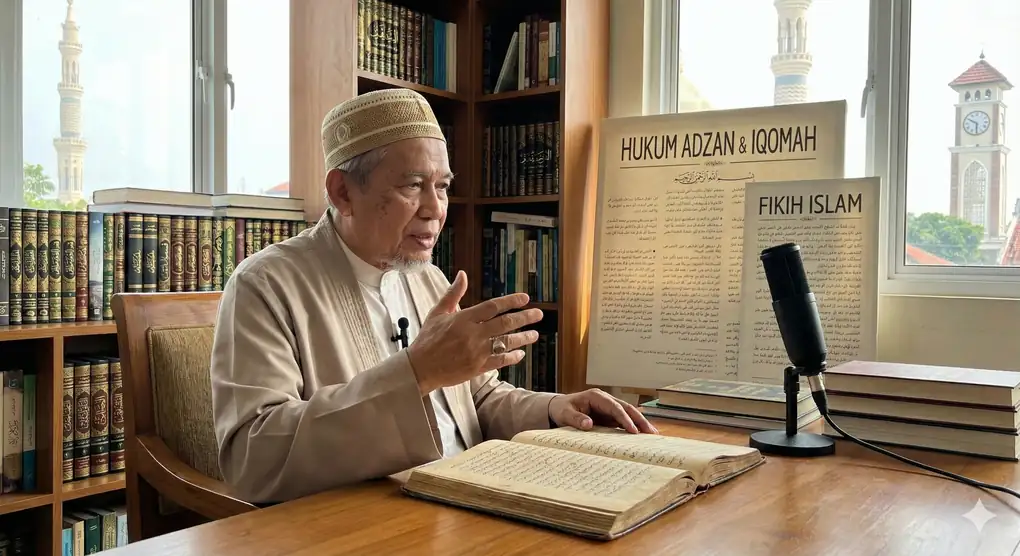

Drawing from the book Asna al-Matalib (Volume 1, pages 125-126), this article will thoroughly examine the definition, jurisprudential rulings, and historical origins of the Adhan—a noble practice that remarkably originated from a dream.

The Meaning of the Adhān and Iqamah

Before proceeding further, we need to properly define the Adhān. In fiqh texts, this discussion is usually opened with the definition of the Adhān according to language and terminology.

Linguistically, the words Adhān, al-adzin, and at-ta’dzin have the meaning of notification (al-i’lam). Therefore, the meaning of Adhān linguistically is an announcement or notification to the general public. This refers to the word of Allah in Surah At-Taubah verse 3: “And an announcement (Adhān) from Allah and His Messenger…”

Meanwhile, the understanding of Adhān according to Islamic law terminology is a specific utterance or phrase used to indicate the beginning of the time for obligatory prayers. Therefore, if there is another notification in the mosque but does not use that specific phrase, it cannot be called an Adhān in the context of performing prayers. We cannot understand the meaning of Adhān linguistically except as a general notification, but according to Islamic law, it has a standard rule.

As for the meaning of Adhān and Iqamah, they are two calls with different functions but come as a package. If the Adhān functions to call people who have not yet arrived at the mosque, Iqamah is a call that prayer will be established immediately for those who are already prepared in the place of prayer.

Here is the original wording from the book Asna al-Matalib regarding this definition:

( الأذان والأذين والتأذين بالمعجمة لغة الإعلام … وشرعا قول مخصوص يعلم به وقت الصلاة )

The History of the Adhān and Iqāmah: Beginning with a Dream

The history of the Adhān has a very interesting story. In the early days in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad SAW and his companions were once confused about how to gather people for prayer on time.

In the history of the Adhān and Iqamah, the idea of using a bell (naqus) like Christians or a trumpet like Jews once emerged. However, the Prophet was not pleased with this. Eventually, a solution came through a dream of a companion named Abdullah bin Zaid bin Abdi Rabbihi.

The following is a historical ḥadīth regarding the Adhān narrated with a ṣaḥīḥ chain of transmission by Abū Dāwūd, as quoted in the book:

لما أمر النبي – صلى الله عليه وسلم – بالناقوس يعمل ليضرب به الناس لجمع الصلاة طاف بي وأنا نائم رجل يحمل ناقوسا في يده فقلت يا عبد الله أتبيع الناقوس فقال وما تصنع به فقلت ندعو به إلى الصلاة قال أولا أدلك على ما هو خير من ذلك فقلت بلى فقال تقول الله أكبر الله أكبر إلى آخر الأذان

Abdullah bin Zaid narrated: “When the Prophet ordered the making of a bell to call people to prayer, I dreamed of someone carrying a bell. I asked, ‘Will you sell the bell to us so we can use it to call to prayer?’ The man replied, ‘Would you like me to show you something better than that?’ He then taught the phrases ‘Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar’ until the end of the Adhān.”

The next day, Abdullah bin Zaid reported to the Prophet SAW. He said that it was a true dream (Ru’ya Haq) and ordered Abdullah to teach Bilal bin Rabah because Bilal’s voice was louder and more melodious. Umar bin Khattab, upon hearing Bilal’s voice, rushed out of his house because it turned out he had had the same dream.

The Rulings of Adhan and Iqamah in Islamic Jurisprudence

After understanding the definition of the Adhān linguistically and terminologically, as well as its history, what is its legal status?

The Shafi’i scholars affirm that the ruling of the Adhān is Sunnah Kifayah for obligatory (Maktubah) prayers. This means that if someone in a village has already proclaimed the Adhān, the obligation is removed from others. However, if an entire village abandons it, they lose the virtue of that Sunnah.

Some important points regarding the ruling of Adhān:

- The ruling of the Adhān Before Congregational Prayer This is a confirmed Sunnah. Its purpose is to proclaim and call people to gather. The ruling of the Adhān before prayer is still recommended even if a person prays alone (Munfarid). The book Asna al-Matalib mentions: “It is Sunnah to perform the Adhān for a Munfarid (a person praying alone) even if he hears it from others.”

- The Ruling on Calling the Adhan Before Its Time: Because the fundamental definition of the Adhan is the announcement that a prayer time has begun, an Adhan called before its designated time is considered invalid as a call to prayer. The only exception is the first Adhan of Fajr, which serves the purpose of waking people up; however, the actual Adhan marking the prayer time must still be called after the time has entered. If performed prematurely without a valid Shari’i purpose, it loses its primary function as i’lam (the notification of time).

- Raising the Voice It is recommended to raise the voice during the Adhān. Abu Sa’id al-Khudri narrated that the reach of the mu’adhin’s voice will be a witness for him on the Day of Judgment.

هو: أي الأذان (والإقامة سنتان) على الكفاية … (ويسن) الأذان (للمنفرد) بالصلاة (ولو سمعه) من غيره

Specific Rules: Women, Combined Prayers, and Making Up Missed Prayers

The book Asna al-Matalib provides interesting details that are often overlooked in discussions of the definition of the Adhān in general terminology.

- Women and the Adhān: Is it permissible for women to give the Adhān? This book explains that it is sunnah for women to perform the iqamah for other women, but it is not sunnah for them to loudly proclaim the Adhān. If a woman gives the Adhān in a soft voice (only heard by herself), it is permissible and becomes a reward for dhikr. However, if she raises her voice in a place where non-mahram men are present, it is Ḥarām due to the potential for fitnah from her voice.

- Adhan for Qada and Combined Prayers: If someone is making up (replacing) several prayers at once or performing combined prayers (for example, combining Maghrib and Isha), the rules are unique. They only need to perform the Adhan once for the first prayer, then iqamah for each prayer.

- Example: When combining Maghrib and Isha prayers, only one Adhān is called at the beginning, then iqamah for Maghrib, and iqamah again for Isha.

Conclusion

From the discussion above, we can see that the adhan linguistically is a general announcement. Whereas, the meaning of the adhan terminologically is the notification of the entry of prayer time and a symbol that has a strong historical basis from the dreams of the companions which were confirmed by the Prophet.

Hopefully, this explanation regarding the definition of the Adhān as a call to worship, along with its rulings and history, will increase our devotion when we hear it resounding.

Reference

Zakariyā al-Anṣārī, Asnā al-Maṭālib fī Sharḥ Rawḍ al-Ṭālib, with a ḥāshiyah by Aḥmad al-Ramlī, edited by Muḥammad az-Zuhrī al-Ghamrāwī (Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿah al-Maymānīyah, 1313 H; repr. Dār al-Kitāb al-Islāmī), vol. 1, pp. 125-126.